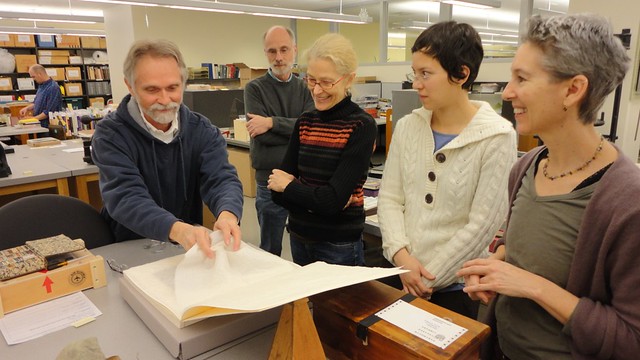

A few weeks ago I was contacted for information regarding an item shown in the photo banner of our department home page. The question was a surprising one but it made me think about the photos in the banner, the rationale behind them and the sometimes subliminal messages I am sending.

Looking from left to right there are six photos (actually nine but the last three are generic images of the Library) and each represents an activity or important relationship with other departments in the Library.

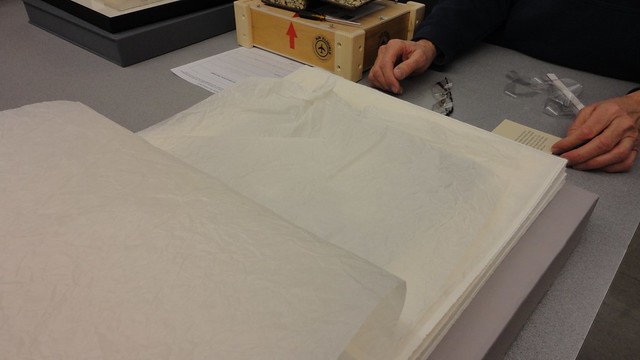

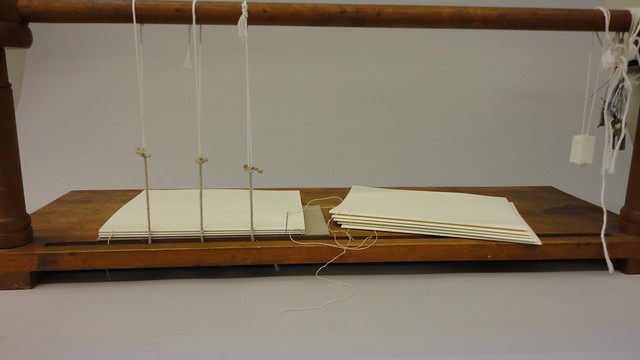

1. Digital conversion & digital preservation: A leaf from the Brut Chronicle being scanned. Preservation Services staff have worked hard to raise awareness of the need for pre & post digitization conservation. The Brut was taken apart for cleaning and rebinding, and in the middle of that treatment it was scanned. Preservation staff have also been responsible for the actual scanning of some materials and Preservation staff are collaborating across the organization to manage & preserve digital resources.

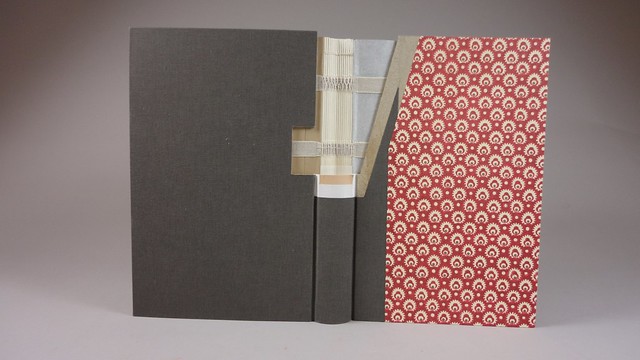

2. Conservation: Brushes symbolize book and paper conservation.

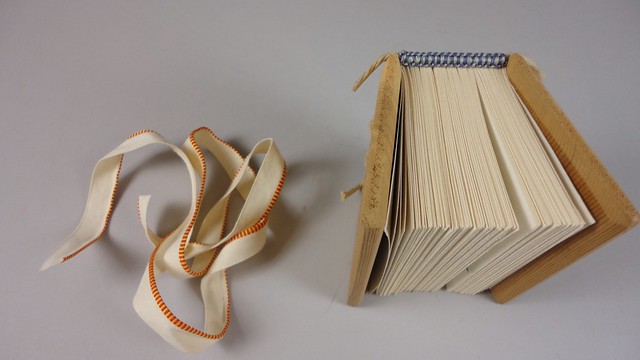

3. Non-book preservation: Our department is responsible for ALL of the Library's resources. This staged photo for a film preservation presentation is a graphic reminder of how NOT to handle film. This image is found on the slide show of our blog and is one of my favorites, the title of the film being, "Why I came to Dartmouth".

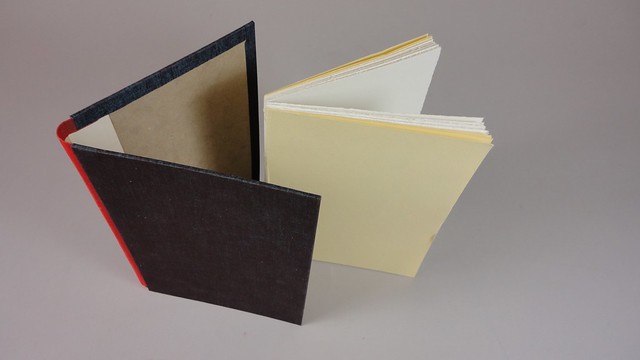

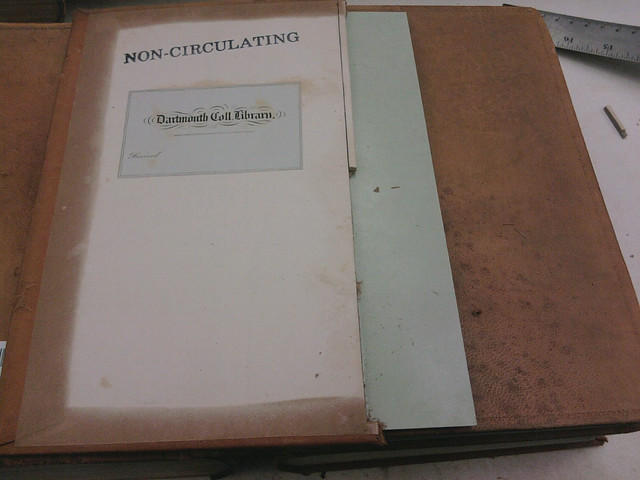

4. Conservation documentation: Each day Preservation staff repair books from the circulating collections and use their considerable expertise to repair items from the Rauner Special Collections Library. We typically document before and after treatments for items from that collection. This was also the photo that generated the question -- where to obtain the color bar.

5. New Book Processing: Preservation Services is reponsible for attaching book plates, call number labels, and security strips in all newly received items for the collection. The "hand model" is Maxine Cameron, who was a key member of the preservation team up until her retirement in 2010.

6. Circulation: The reason for our being. Access and preservation go hand in hand.

Written by Barb Sagraves

Another National Preservation Week has come and gone! I hope you had an opportunity to benefit from our tips or attended the “

Another National Preservation Week has come and gone! I hope you had an opportunity to benefit from our tips or attended the “