As a Samuel H. Kress Conservation Fellow, I have been

spending my first post-graduate year revamping Rauner’s Iconography Collection.

The Iconography Collection is an image-based collection which includes prints,

photographs, negatives, albums, and various other materials. In my initial survey of the collection I

found that a number of the top treatment priorities were albums. I decided to focus on treatment of these

albums not only because they were in poor condition, but also because this

allowed me to further explore my interest in album structures.

|

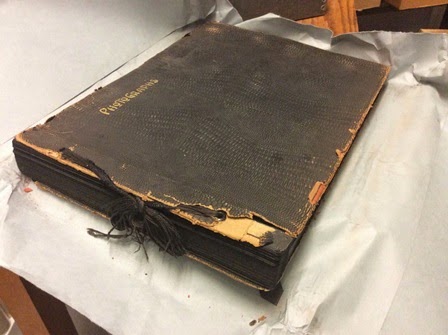

| Example of a damaged album discovered during the survey. |

In conservation we try to preserve the original structure of

the books we work with, but there are times when the original structure is

inherently problematic and must be altered to prevent future damage. I have

found that this is especially applicable to albums. A common condition issue was that either one

or both of the boards were detached.

For the album shown below, I successfully reattached the

boards and preserved the original structure of the album. The detachment occurred between two of the

front pages, and the spine covering had pulled away from the text block. I cleaned the old adhesive from the inside of

the spine covering and the spine of the text block, and then placed new linings

on both.

|

| Carte-de-visit album before treatment, showing detached front board. |

|

| Carte-de-visit album after treatment, showing reattached front board. |

|

| Carte-de-visit album after treatment, showing reattached front pages and front cover left purposefully detached (back cover has been attached to the text block). |

My favorite album from the collection features stunning watercolors from

1857-58 made by Sir Henry Hugh Clifford, who was stationed in Canton, China an

Assistant Quartermaster General in the British Army. While Clifford was stationed in China to serve in the Second Opium War, his meticulous paintings capture serene and colorful landscapes and portray scenes of everyday life in China.

As we are nearing the end of a long, cold winter, this album

has been a treat to work with, and has led me to start fantasizing about warmer

weather and beaches.

|

| Watercolor painting by Sir Henry Hugh Clifford entitled "Sunset, Victoria". |

Prior to treatment, the album was bound in a post-style binding. After close examination, it became clear this

was not the original binding structure and the cover did not add informational

value to the object.

|

| Overall image of album: please note the significant amount of surface dirt on the pages in the upper right. |

|

| Detail of post binding structure: cord strung through two holes through text block and tied together, pages are not secure. |

We decided that removing the album from the binding

completely and storing the leaves in an enclosure was the best solution,

because this will allow for easier access and prevent strain on the pages. While dis-binding the album, I conducted dry

surface cleaning of the pages to remove the highly noticeable,

easily-transferable dirt.

Collectively, these treatments show that, while we strive

toward minimal intervention, altering the structure of bound materials is sometimes

the best course of action to prevent further damage.

Written by Tessa Gadomski