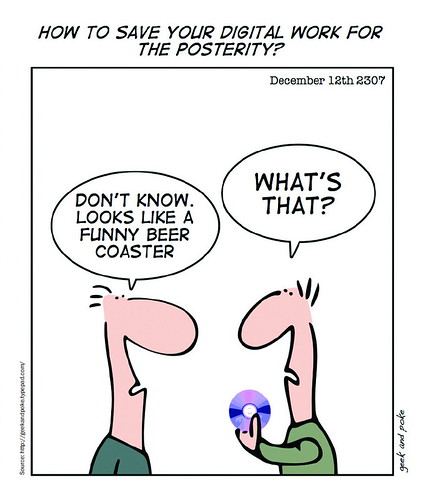

To follow up on my first digital preservation post, I want to talk a little bit about why we need to spend time and energy preserving digital materials. After all, digital materials are just there, right? They don’t fall apart like books or become brittle like paper or warp and shrink like film. So they must be safe, yes? Oh, if only that were the case. Unfortunately, the example shown in the comic below is just one of the many ways that digital materials can become unusable over time.

Perhaps the biggest challenge in preserving digital materials is obsolescence. Obsolescence occurs when a digital object becomes unusable due to new developments in software or hardware. This is something nearly all of us have encountered with programs such as Microsoft Word. Ever noticed that a Word file created in 1990 will not open in today’s version of Word? That’s because the software has changed so much that it is incompatible with files made in previous versions, thus rendering those files obsolete. This kind of software incompatibility happens all the time, and the same thing is going on with new developments in hardware…have you tried to use a floppy disk in your computer recently? If so, you likely discovered that computers are no longer built with floppy disk drives, and so unless you have a computer from 15 years ago, the data on that disk is unreadable.

Another major problem with digital materials is that they do, in fact, deteriorate over time. While this deterioration may not be as evident as it is with photographs or books, it still happens. And again, nearly everyone with a computer has experienced this. Hard drives crash (often unexpectedly and at the most inconvenient times), CDs and DVDs get scratched, and magnetic tapes and other storage media simply lose data or fail altogether as time passes. Bits and bytes themselves, the actual pieces of code from which all digital files are built, can also be slowly damaged or lost over time. All of these forms of content loss due to physical degradation are known as bit rot, and they are a never-ending threat to digital materials.

One digital preservation conundrum that many people don’t consider is the problem of information retrieval. As massive numbers of digital resources are created, each containing hundreds or thousands of files, the ability to organize and locate those files becomes a complicated task, both for large institutions and individual people. Let’s say it’s 2057 and you’re looking for a particular file that you created in 2010. What is the file called? Where did you store it? How are you going to find it among all the other thousands of files you’ve created in the past 47 years? Do you know what format the file is, or what kind of hardware and software you’ll need to open it? Even if the data is not obsolete and the bits are all still there, without this kind of contextual information you won’t be able to use or even find the resource you’re looking for. Libraries and archives are dealing with this problem on a massive scale.A final issue that is not unique to digital materials, but is still of major concern, is the possibility of loss from disaster. This could be a natural disaster such as a hurricane, or a human-caused disaster such as a terrorist attack or even the unfortunate accident like spilling a glass of milk on your computer. No matter how much careful planning goes into the creation and storage of those files, disasters can always come along and destroy them.

So, given all of these methods by which digital materials can be damaged, lost, or rendered utterly useless, it should be clear that there is a very real need for digital preservation action to be taken. I’ll talk about what those actions are in my next post, and what we’re doing here at the Dartmouth College Library to preserve our unique digital collections.

Written by Helen Bailey

This is a great post on the shortfalls of digital storage. It is amazing how many people feel that digital is best and "paperless" is our future. We, at Tameran Graphic Systems, believe that digital images are fine for everyday access and distribution but not for successful preservation purposes. We leave that to microfilm in its various forms since it is unalterable, technology independent, self-sustaining over long periods of time and can be easily converted back to digital whenever necessary. We will check back for your next post to see if you agree!

ReplyDeleteThanks for the comment! I agree that there are many instances for which paper is a much better option for preservation than digital files. Unfortunately, for libraries and archives who are charged with preserving vast quantities of information for future generations, it simply isn't feasible to convert all of their digital resources to analog formats. So while it's important to continue storing certain items on paper and microfilm, it's also necessary to use the best practices available for preservation of digital materials...because some resources will simply never exist in non-digital form.

ReplyDeleteOn a related note, the Digital Curation Centre just published a document called The Role of Microfilm in Digital Preservation. Check it out for more info!

ReplyDeletegood

ReplyDelete