Hello! From Baker Berry Library this is Ryland Ianelli, the newest staff member down here in Preservation Services. I am, first and foremost, a cartoonist, and I received my MFA at the Center for Cartoon Studies in 2010. While I spend about half of my time in Preservation, the other half is spent in Digital Production, and working here these past few months I’ve found that the convergence of these units gives me a unique perspective, especially when my personal passion of cartooning is added into the mix.

When many consider the phrase "comic book collection", images of long cardboard boxes, Mylar sleeves and perhaps a dank parents’ basement come to mind; a far cry from the gorgeous, well-lit and spacious Rauner Library. Yet here Dartmouth holds some of the earliest examples of the comic medium, a crucial part of the DNA of both the American and European comic traditions.

|

| The Adventures of Obadiah Oldbuck, aka, La Historie de Monsieur Vieux-Bois |

First and foremost in the collection is "The Adventures of Obadiah Oldbuck" by Genevan artist Rodolphe Töpffer. It was written under the title "Historie de Monsieur Vieux-Bois" in 1827, and went through several iterations before arriving stateside over a decade later. Töpffer grew up in a highly artistic and academic environment; his father, Adam-Wolfgang Töpffer, was a well-known painter and early practitioner of the art of caricature, and young Rodolphe studied art in Paris before being appointed Professor of Literature at the University of Geneva in 1832.

|

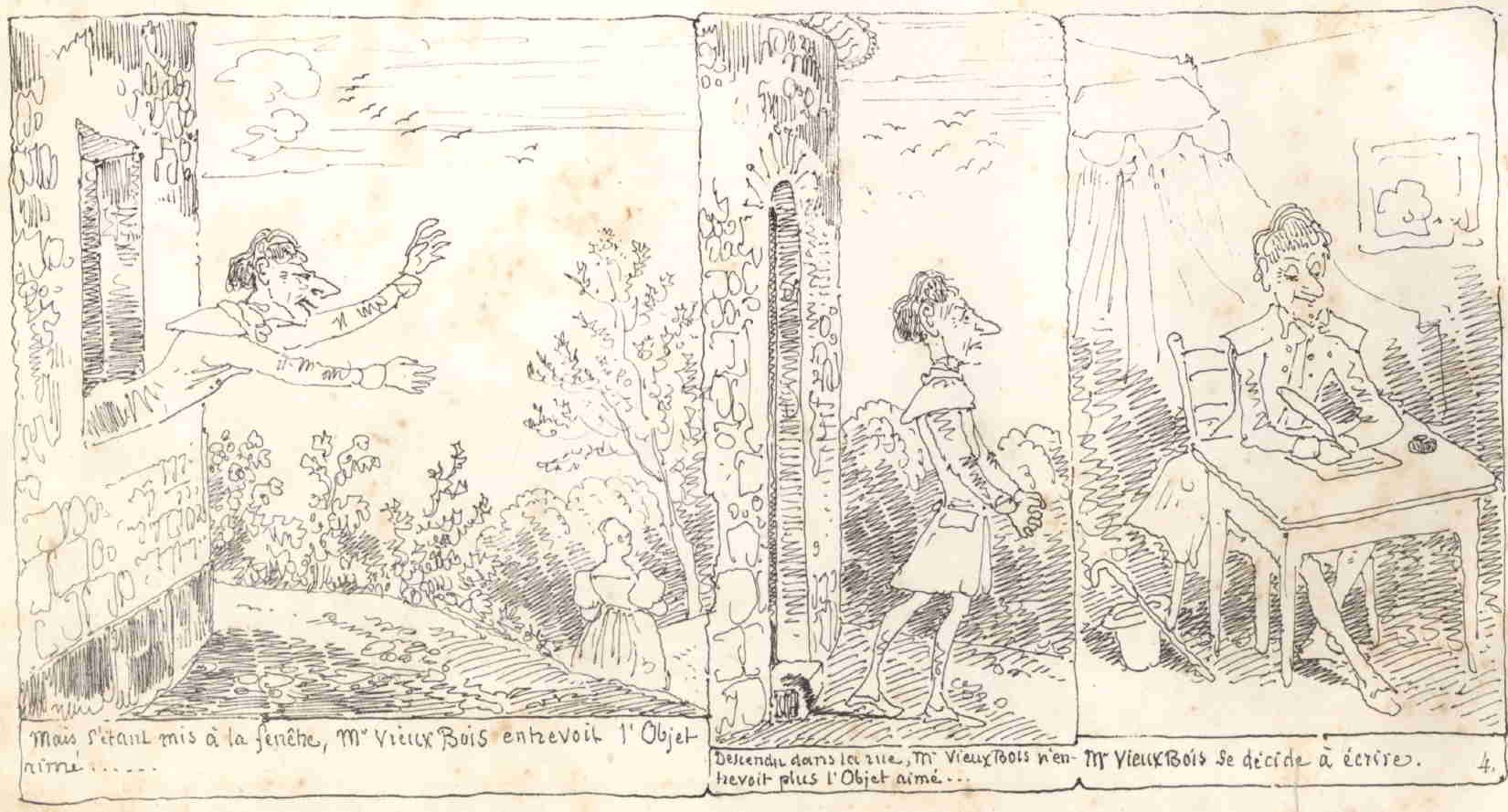

| Page from the 1827 manuscript |

In 1837 Rodolphe began drawing a printable version of Vieux-Bois by the process of autography, a form of lithography. In addition to changing much of the story, Töpffer extended the page width and used only a single tier of panels. He coined the term la littérature en estampes (literature in prints) to describe it, though the term was eventually dropped in favor of bandes dessinées (designed strips, or commonly, comic strips). Töpffer implicitly understood that he needed a new vocabulary, both literal and visual, to adequately describe his goals.

|

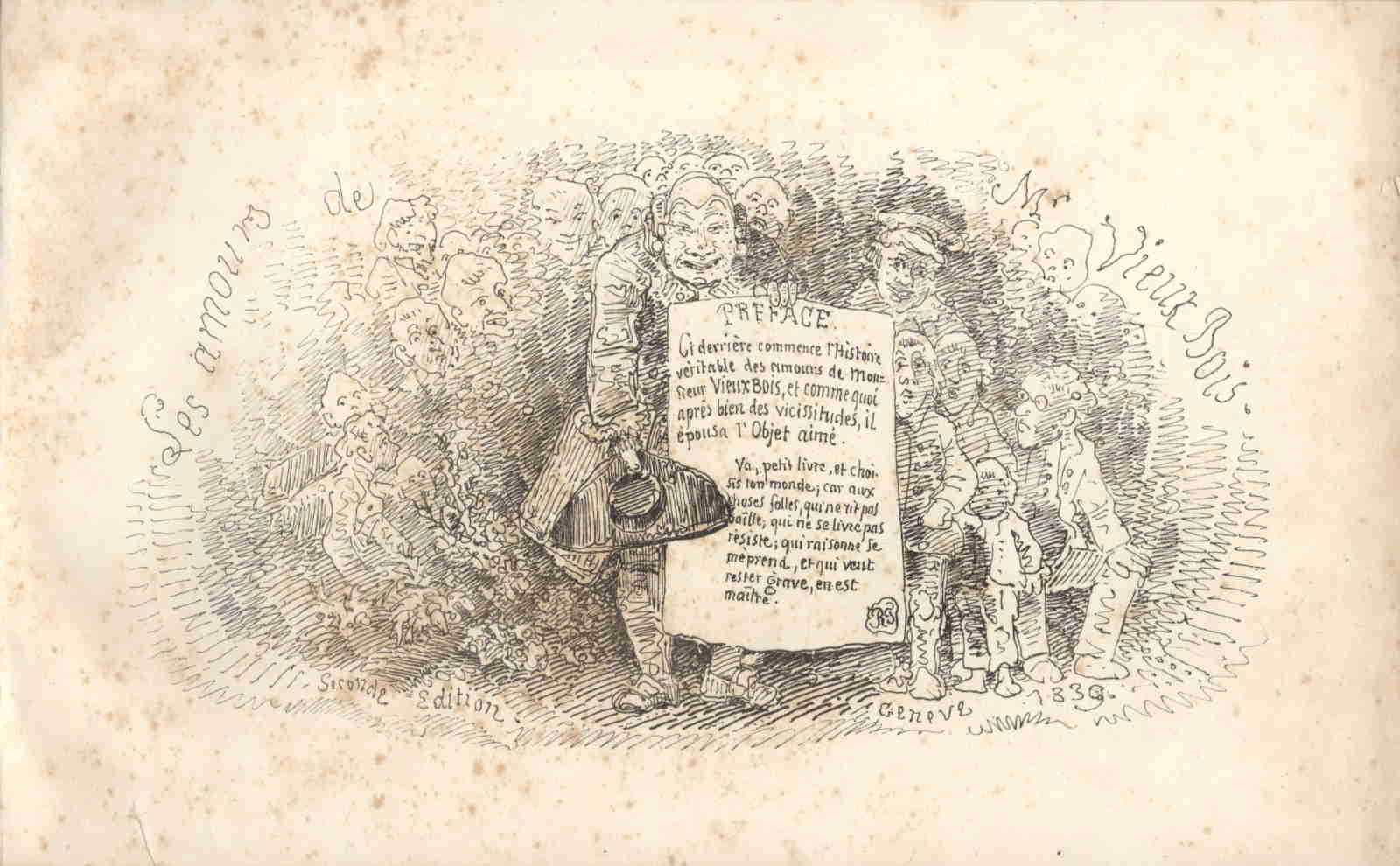

| Page from Töpffer's 1839 edition |

The books themselves were distributed by Töpffer personally among a network of bookshops across Europe. The differences between this edition of Vieux-Bois and its later versions are certainly fascinating, but the similarities tell us more. The pacing, storytelling, humor and whimsically exaggerated character design were the essential framework of Töpffer's project and its later iterations.

|

| Cover image from Töpffer's 1839 edition |

These iterations are where the subject becomes a bit tricky: after the tiny initial print run ended, bootlegged copies began appearing in Paris bookshops. And, keeping in mind that Xerox technology was still to be developed, this meant the bootleg copies were completely redrawn versions, copied from the originals by a different artist and sold without Töpffer's knowledge.

The first French bootlegged copy came out in early 1838, and later that year Töpffer himself redrew the book, selling it in direct competition with his own bootleg. There was not much of a contest between the two; the bootleg was far more crudely drawn, and omitted many of Töpffer's details, while Töpffer's newer version refined the storytelling and added details. However, when an English publisher decided to make his own version it was the French bootleg that was used as a basis instead of the original.

|

| Cover image from French bootleg edition |

As it turned out the English copy-of-a-copy was a good sight better than its source material. This was the version that was eventually brought to America by Wilson and Company Publishing, with the name changed to "The Adventures of Obadiah Oldbuck." The unknown English artist added far more atmospheric flourishes than the French version, while the overall layout and pacing of Töpffer’s originals carried through both versions. "Obadiah Oldbuck" also has the impressive distinction of being the first comic book available in America.

|

| Page from Obadiah Oldbuck |

These complications arising from multiple authors and print runs are a common thread throughout the history of comics scholarship, highlighting the importance of preservation. Such disposable pamphlets are notoriously ill-cared for, and a multiplicity of versions means one edition of the same comic could be considered disposable while another essential. Entire comics histories have been lost due to lack of perceived value. Rauner and Preservation Services have done a truly exceptional job in restoring and making this fascinating piece available.

"Go, little book, and choose your world, for at crazy things, those who do not laugh, yawn; those who do not yield, resist; those who reason, are mistaken, and those who keep a straight face, can please themselves."

-Rodolphe Töpffer, 1839

If you're interested in reading more about Rodolphe Töpffer, here is an excellent article on him by Patricia Mainardi: http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/index.php/spring07/145-the-invention-of-comics. Also, scholar David Kunzle's books on Töpffer are indispensable.

Written by Ryland Ianelli.